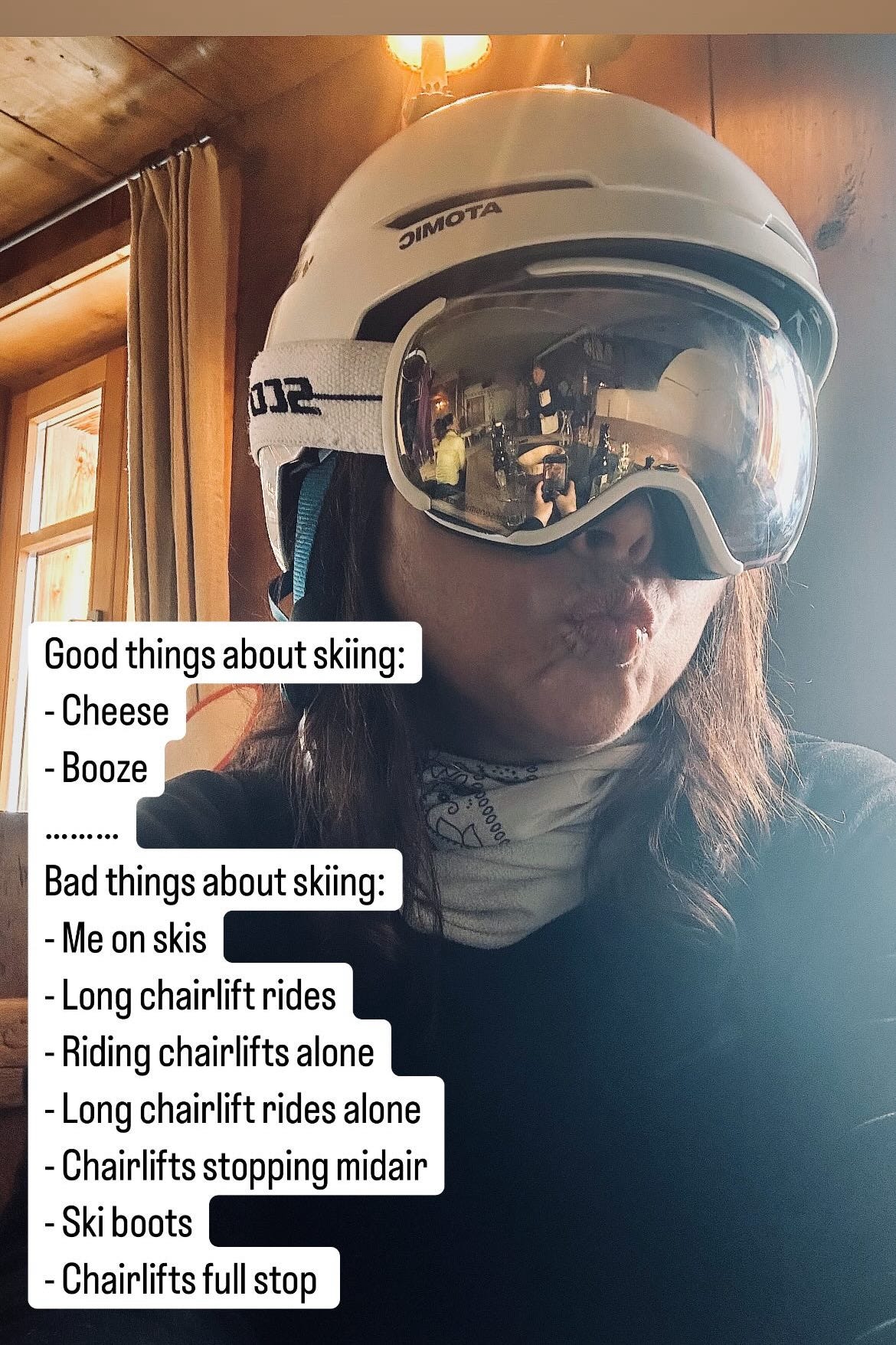

Why Skiing (Badly) is a Metaphor for (My) Life

Rhonda reconciles herself to being a little bit (or a lot) shit at just about everything, especially making decisions.

I was already about 44 when I first took to the slopes, on a family holiday, and while my boys (then around 9, 8 and 5) had all progressed to reds by the end of the first morning, I was still doing Bambi on Ice impressions by the end of the first week and had somewhat of an inkling that I would never be making it to the Olympics.

Such is the way.

As my most recent ski instructor, in the lively Swiss resort of Davos, told me, I’m at a threefold disadvantage when it comes to becoming even faintly competent on the slopes: I’m old (ouch), I’m a woman/mother (more inclined to angst about what would happen to my kids if I fell off the side of a mountain), and I’m an overthinker.

I can’t argue with any of this. At fifty-six, I’m not exactly old, but apparently I’m old in skiing terms (which is a bit like being told you’re going to be a ‘geriatric mother’ with your second baby, aged thirty-five).

I know this because for the first time when being fitted with my ski equipment, I was asked my age, and when I enquired why that was relevant, learnt it’s because of changes in balance, joint flexibility, and muscle mass that need to be taken into consideration. So be it.

And yes I’m very definitely a woman and I worry about all sorts of things from breaking my wrist and not being able to earn a living for a few months to being heli-lifted off a mountain with a broken neck. Or death.

Because that, as far as I am concerned, is the problem with skiing: the ‘better’ you get, the more extreme situations you put yourself in. And so many of the ‘good’ skiers I know have been choppered off mountains and now have bits of metal in their legs. And these are the lucky ones.

On the other hand, my recent ski trip really brought home to me that overthinking is a real problem not only on the slopes, but in my life (hey, I’m a Libran with a Virgo ascendant; I am doubly-fucked astrologically).

For two days, my instructor bravely battled the contents of my mind as I delivered up mental block after mental block and even began to get worse. It’s maddening when get yourself so spooked, you stop being able to do things you’ve been fine with in the past.

Of course, overthinking begets panic, and then all hell breaks loose and you find yourself in freeze mode on the side of a mountain wailing, ‘I can’t do this,’ and that’s no use at all because basically you do have to get down the fucking thing and your ski instructor’s eyes are swivelling in his head.

What I did find worked this time – as they do in life, no matter how simple they are, or perhaps actually by virtue of how simple they are – are some mantras.

Necj my instructor was continually pointing out to me what a ‘rightie’ I was, favouring one leg and one side of my body over the other, which mean I’d either drag the other one or leave it behind and have to lift it up. A nonsense technique but one that probably reflects some kind of general imbalance between the left and right hemispheres of my brain.

But telling me I was doing this had no effect, because most of the time I couldn’t feel I was doing it at all. Or it even made it worse, because it tensed me up. And being tense is the very worst thing with skiing, as with riding a horse or a lot of other sports or actually anything in life. It’s all about the flow.

However, flow is not so easy to achieve when all you can think about is the edge and the sheer-drop beyond it…

The lightbulb finally came on when Necj told me to ‘commit to the turn’, rather than resist it. This echoed what a previous instructor in the French Alps had told me when he pointed out that I was fighting the snow, when in fact I needed to caress it – ‘Make love to it!’, in fact (FNARRR, those cheeky French boys…).

So now, at every turn on the heavily cambered blue that was causing me such grief, I stared the mountain down instead of avoiding it with my gaze, and rather than resisting the turn, gave myself to it. And each time I did, I chanted, ‘Commit, commit’. I I felt quite deranged, but it worked.

‘Mantra’ comes from a Sanskrit word meaning sacred message, charm or spell, and it did indeed feel like I was sending myself a message: the message that I wouldn’t fall down the mountain if only I relaxed into what I was doing. Or in fact casting a magic spell on myself.

Mantras soothe the nervous system, decreasing the heart rate, blood pressure and stress hormone levels. I chant some daily in my kundalini yoga and meditation practice, and I also have some at the ready when I’m travelling and feel a little out of control of circumstances. Even mantras such as ‘It’s all going to be fine’, childish as they sound, work. Because things normally are fine – most of what we spend our lives worrying doesn’t ever come to pass.

The mountains are a great place for reflecting on life. You have lots of time going up and down on chairlifts and gondolas, soul-stirring vistas upon which to gaze, and, if you’re lucky, some lovely long runs on which to contemplate the universe and your speck-like place in it – to get some perspective on it all.

But my new mantra really got me thinking about my overthinking…

I was, I saw clearly, spending too much time dithering. In particular, I’d just spent a whole eight months doing my own head in about a romantic entanglement that I knew from the start was wrong for me on many levels.

So why had I kept going back and picking it up and turning it over and over in my hands like a sparkly but dangerous jewel? Why not go with my own gut instinct instead of trying to gaslight myself into accepting something I wasn’t happy about?

I’d needed to make a decision – ‘no’ – and commit to it, no matter how unsatisfactory I found that decision, no matter the regret I will always feel.

I’ll always be rubbish at skiing, I’ve accepted that. Does that mean I’ll always be rubbish at life?

Maybe so, but I can get less rubbish. Nothing and nobody is perfect.

In skiing, you have to lean forwards despite the fact you’re going downhill. It feels unnatural, unsafe. But it’s the only way to get down – so you might as well make it easier for yourself and embrace the movement, the changes, and yes even the speed and the feeling of loss of control.

Commit, commit.